ALL CONTENT ©2003GazetteArchive

21 MAY 2003

The Gazette will return after summer break on JUNE 11

Latest from Sqn HQ:

++PROMOTIONS: Wulf to CPT -++

++CD SOARING Last chance to order!++

THE REAL-LIFE 607 SQUADRON

Aircraft: Gloster Gladiator, Westland Wapiti, Hurricane I, IIc, Spitfire variants

Badge: A winged lion salient, the hind legs also winged. The badge was an official authorisation of an unofficial badge in use by the squadron.

No 607 Squadron was formed on 17 March 1930 at Usworth as a day bomber unit of the Auxiliary Air Force. The former landing ground at Hylton used during World War One was in course of preparation as the squadron's base, but it was not until September 1932 that any personnel could move to the site. Next month a Gipsy Moth arrived to allow flying training to commence, and in December the first Wapitis were received. These were replaced by Demons. No 607 being redesignated a fighter squadron on 23 September 1936. In December 1938 conversion to Gladiators began and these were taken to France in November 1939 to join the Air Component of the BEF. In March 1940 Hurricanes began to arrive and within a few days of the German invasion in May had completely replaced Gladiators. With its airfields overrun, the squadron moved back to the UK to re-equip and in September moved south to defend southern England during the Battle of Britain.

Excerpt from 607 Sqn History with the GLOSTER GLADIATOR

No 607 Squadron

Usworth, December 1938 to October 1939.

Acklington, October 1939 to November 1939. Croydon, November 1939. France,

December 1939 to March 1940.

Code letters: "LW", changed to

"AF" in September 1939.

Serials:

K6137, K6147, K6149, K7931, K7965, K7967,

K7980, K7982, K7983, K7988,

K7989, K7992, K7995, K7996, K7997, K7998,

K7999, K8000, K8020, K8026,

K8030.

Notes:

K6137 was an ex-No 72 Squadron received

12/38; crashed at St. Ingelvert after engine failure, 7/2/40.

K7995; later to Gosport Station Flight.

K7996; crashed in bad weather, 26/3/40, P/O

Whitty safe.

K8000; collied with K8030, Vitry, 23/3/40;

P/O Radcliffe killed.

K8030; collied with K8000, Vitry, 23/3/40;

F/O Graeme killed.

607 Sqn Roster

1939

GDCraig

George Dudley Craig OBE of Corbridge practised as a Solicitor and joined 607 Squadron AuxAF in 1937. He served in France and throughout the Battle of Britain, taking command in March 1941. After being shot down over France in November 1941 he was a POW and escaped but was recaptured. Released from the RAF in 1945 he rejoined the AuxAF in 1947. He died in 1974.

Officer Commanding: J.Vick

W.Baranski

L.D.Barnes H.I.R.Barrow

J.M.Bazin W.F.Blackadder

C.E.Bowen

N.Brumby P.A.Burnella-Phillips

V.A.Carter

G.D.Craig W.G.Cunnington

I.B.Difford

G.J.Drake G.J.Elliott D.Evans

A.D.Forster J.A.Frey

A.Gabszewicz

W.E.Gore M.Gorzula C.L.Gould

D.L.Gould G.A.Hewett

M.R.Ingle-Finch

M.M.Irving P.J.Kearsey

M.C.Kinder

Z.Kustrzynski J.Lansdell

W.Lazoryk

J.D.Lenahan S.V.McCall

W.W.McConnel

A.R.Narucki W.P.Olensen

J.Orzechowski

S.B.Parnell G.Radwanski

I.M.W.Scott

R.A.Spyer P.J.T.Stephenson

J.M.Storie

J.E.Sulman F.Surma

G.H.E.Welford

W.H.R.Whitty B.A.Wlasnowolski

Wydrowski John Sample

John Sample

John Sample

DFC was an estate agent from Morpeth Northumberland. Gaining his wings with 607

Sqn then taking command of 504 Squadron in May 1940 he was awarded the DFC. He

was killed in a flying accident on October 28th 1941 when with 137 Squadron of

Whirlwinds.

P2617/AF-F, Hawker Hurricane I, preserved at the

RAF Museum,

RAF/607 Squadron

marks, Hendon, England, 7/2/1993

607 Sqn PILOT HISTORY

GOOLD,W.A

Last

Name; Goold

First Name; Wilfred Arthur

Serial No; 403135

Rank; Flight Lieutenant

Decorations DFC Squadrons 607 Sqn RAF

Posted to 607 Sqn in Burma as a Sgt in December 1942. 20 Dec 42 - Escorting Blenhiems and Bisleys, Bombing Magwe, is chased at low level until the Oscar behind him crashes.(1.0.0) He flew on numerous ground-attack and bomber-escort missions until the end of 1943, when he converted to Spitfires. By this time he had been commissioned. 20 Jan 43 - Probably destroys a Nakajima Ki 43 Oscar, and damages another. (1.1.1) 11 May 43 - Destroys one Oscar and damages a second. (2.1.2) 18 May 43 - Destroys one Oscar and damages two others. (3.1.4) 21 Feb 44 - The Spitfires of 607 Sqn RAF were scrambled when radar detected over fifty aircraft. The Spitfires made contact and the sky was wreathered with vapour trails during the engagement, Goold claimed one damaged. (3.1.5) By September, when he had become a Flight Commander, he had brought his score of Japanese aircraft to 5, and was awarded the DFC.

William Hubert Rigby Whitty DFC

Squadron Leader William Hubert Rigby Whitty DFC, RAF no. 90288

William Whitty was born on 27 March 1914 in Litherland, Lancashire.

He went to Liverpool College and was at Liverpool University from 1931 to 1935, studying Engineering.

He was commissioned in 607 Squadron (County of Durham), AuxAF on 7 March 1938 and was called to full-time service on 7 September 1939 and at the same time promoted to Flying Officer.

In October 1939, 607 Squadron, AuxAF was based at Usworth.

At 12:40 on 17 October a section from ‘B’

Flight of 607 Squadron was scrambled to seek German seaplanes that had been

reported off the coast. Flight Lieutenant John Sample (Gladiator K7995/AF-O),

Flying Officer Dudley Craig and Pilot Officer Whitty (Gladiator K8026/L) headed

out to sea, where at 13:30 they intercepted a Do18 flyingboat some 25 miles of

the coast. This was 8L+DK from 2/KüFlGr606 flown by Oberleutnant zur See

Siegfried Saloga, which they attacked individually from astern.

The Dornier was not shot down at once,

struggling eastwards for about 35 miles before crashing into the sea. The crew

were rescued by a British trawler and made prisoner.

The squadron flew from Usworth to Croydon on 13 November and two days later flew to Merville in France.

On 26 March 1940 he crashed in bad weather with Gladiator K7996 but survived.

The Squadron started to re-equipped with

Hurricanes in April 1940.

During this time Flying Officer Whitty served

in B Flight.

At 05.15 on 10 May Yellow Section of A

Flight, 607 Squadron, encountered a number of He111Hs of II/KG1 east-north-east

of Douai. One of the Heinkels were claimed by Flying Officer Bill Gore

(Hurricane P2573 AF-A).

These bombers were also intercepted by Whitty

(from B Flight). He reported:

“I had just arrived [at dispersal] when my

Flight Sergeant pointed out aircraft bombing Cambrai. I took off and caught two

flying together and got one He111 – which crashed near Mons – and got a burst

at the second on his port motor before he got into cloud.”

7/KG1 lost an aircraft in this engagement

when it crashed near Hinacourt, about seven miles south of St. Quentin.

Oberfeldwebel Kurt Buchholz, the pilot, was captured by French forces, but the

remainder of his crew were killed.

On 15 May Squadron Leader Lance Smith

(Hurricane P2870) of 607 Squadron led five Hurricanes of 607 Squadron’s B

Flight and six Hurricanes of 615 Squadron’s A Flight in a escort of a dozen

Blenheims (three of 15 Squadron and nine of 40 Squadron), which were to bomb

the bridges over the Meuse.

Before reaching the target they encountered

Bf110Cs plus Bf109s from Stab III/JG53 at 11,000 feet. In the ensuing combat

Squadron Leader J. R. Kayall of 615 Squadron claimed two Bf110s while Flying

Officer H. N. Fowler (Hurricane P2622) from the same squadron claimed a

probable Bf109 before being shot down himself (he parachuted safely but was

later taken PoW). 607 Squadron claimed two Bf109s shot down, one by Whitty, who

reported seeing the pilot bale out of the aircraft he attacked, and the other

by newly attached Pilot Officer Bob Grassick of 242 Squadron’s B Flight.

Squadron Leader Smith was shot down and killed in this combat.

Three Hurricanes were claimed by III/JG53 and

were credited to Hauptmann Werner Mölders, Oberleutnant Heinz Wittenberg and

Leutnant Georg Claus, while two of the Blenheims were shot down by Bf109s of

1/JG3 encountered when north-west of Charleroi.

Whitty was in France with 607 until it was withdrawn to Croydon on 20 May 1940.

He served with the squadron throughout the Battle of Britain.

On 7 September 1940 he was promoted to Flight Lieutenant.

He was posted away to 56 OUT, Sutton Bridge in November, instructing there on Hurricanes until March 1942.

He was promoted to Squadron Leader on 1 December 1941.

Whitty then instructed at 24 EFTS until

February 1944, when he was posted to Bomber Command.

He joined 76 Squadron in July 1944, flying

Halifaxes and went to 640 Squadron at Leconfield in February 1945, again on

Halifaxes.

On 26 October 1945 he was awarded the DFC.

Whitty ended the war with 1 shared biplane victory and a total of 2.

He went to Transport Command in June 1945 and joined 158 Squadron at Lissett and was with it until November.

On 14 June 1946 he was awarded the DFC (US).

Whitty was released from the RAF in 1946, as a Squadron Leader.

He later went to live in Canada.

Joseph Robert Kayll, from Sunderland, was born in 1914 and was flying from 1934. He joined 607 AuxAF and served in France. In May 1940 he took command of 615 Squadron and was given the double award of DFC and DSO, being decorated by the King on June 27th 1940. He was in action throughout the Battle of Britain. He was shot down and captured in July 1941, he escaped and was re-captured in 1942. Kayll was eventually freed in May 1945. He left the RAF in 1945 as a Wing Commander. He received the OBE in 1945 for his escape work as a POW. He also rejoined 607 AuxAF and became a JP and Deputy Lieutenant in his native Durham. He died in March this year.

Vickers Supermarine Type 380

Spitfire LF.XVIe TE462 - from 607 Sqn

A HISTORY OF 607 Sqn - and USWORRTH AIRFIELD

At the time of closure of the airfield at Usworth, on 31 May 1984, a history of aircraft use could be traced back over a time period spanning almost seventy years to the latter stages of the First World War.

The airfield that subsequently became Sunderland Airport started life in October 1916 as a Flight Station for 'B' Flight of No. 36 squadron and was originally called Hylton, although when being prepared it was known as West Town Moor. Due to an increase in German bombing raids and the heavier commitment of RNAS aircraft in France, the Royal Flying Corps took over the task of Home Defence, setting up a number of squadrons, with flights spread over the length of the British coastline. The Northeast was protected by No. 36 Home Defence squadron, which was formed by Capt. R. O. Abercromby at Cramlington on 1 February 1916. Plans for 'B' flight were put in place in 1916 as a consequence of the recent Zeppelin raids on the area. An area of land just North of the river Wear between Washington and Sunderland was set aside for the new landing field.

No. 36 Home Defence squadron of the Royal Flying Corps operated B.E. 2c's and B.E. 12's, their task being the defence of the coast between Whitby and Newcastle. The main base was at Cramlington outside Newcastle, flights being detached to Seaton Carew and Ashington as well as Hylton. On 27 November 1916 a patrol of B.E. 2's flying from Seaton Carew intercepted two groups of Zeppelins over the North East coast, Lt I.V. Pyrott destroyed LZ34 which crashed into the mouth of the Tees, the sight of this caused the other airships to turn back. The only other action that the squadron was involved in was the unsuccessful attack on the Zeppelin L42 over Hartlepool on New Years Day 1918.

The occupation of Hylton by No.36 squadron introduced the Wearsiders to the sight and sound of aircraft. However this introduction did not go entirely smoothly. On 24 May 1917, Lt Phillip Thompson took off from Usworth to air test a newly fitted machine gun, over the sea, in preparation for that evenings anti-Zeppelin patrols. On his return from the coast at 8:45 p.m. the pilot observed a crowd on the Green at Southwick. In order to gain a closer look the pilot brought his aircraft low over the Green. Unfortunately whilst flying towards the sun the pilot failed to observe a large flag pole on the center of the Green. The port wing of the aircraft was torn off by the impact, the aircraft falling to the ground at the corner of Stoney Lane. Remarkably the pilot survived the mishap, but unfortunately five people were killed and eight others injured on the ground.

By August 1918 Hylton was in use by 'A' Flight and continued as such until the Armistice when it was just beginning to become known as Usworth. No. 36 squadron's HQ moved here in November 1918, the main equipment now being Bristol F.2b's. The Bristol F2b was one of the best fighters of the War despite being a two seater, it was used as a single seater with a sting in the tail. It was powered by a 275 hp Rolls Royce Falcon inline engine, with a top speed of 125 mph at sea level compared with the 90 mph of t he B.E. 12's.

When the squadron was ready for its new role it moved once more in November 1918 to Ashington leaving a detachment at Hylton and with peace being declared, it was finally disbanded on 13 June 1919.

The only known reminder of 36 squadron remaining in the North East is a stone monument erected on Anfield Plain in memory of Sgt Pilot Arthur John Joyce (9935) who was killed when his F.E. 2b, A5740, crashed on patrol at Pontop Pike on 13 March 1918. Sergeant Joyce had started his fateful mission from Usworth that evening.

With the ending of the first world war the area around Usworth was to return to non-flying use. In the manner of many First World War aerodromes, Usworth languished unused for over a decade, apart from at least one visit by Alan Cobham's Flying Circus, until nominally being re-activated on March 17 1930.

The new airfield was sited alongside the B1289 road between Washington and Sunderland, with the flying field to the South of the road and ancillary buildings to the North of the road. The new airfield had been designed to accommodate one squadron of the recently expanded Royal Auxiliary Air Force. This was to be No.607 (County of Durham) Squadron. North Camp was provided with living quarters and dining facilities for Officers, NCOs and airmen. It was initially proposed to erect canvas Besoneaux Hangars on the South camp, however these were rejected in favour of the erection of a large Lamella Hangar. The South Camp also housed the Squadron Office, pilots huts, armory, photographic hut and bombing training aids. Alongside the railway were the firing butts.

It was not until September 1932 that the airfield was ready to receive personnel under the command of the Hon Leslie Runciman. No. 607 squadrons pilots and groundcrew came from all walks of life locally and were trained by a nucleus of regular RAF NCO's and airmen of various trades, and had two Qualified Flying Instructors with them, a Flt Lt Manton, and Flying Officer Turner. The following month the first aircraft, a Gypsy Moth, which was soon followed by two Avro 50N trainers, arrived for flying training to commence for No. 607 squadron. The first operational equipment for No. 607 squadron, the Westland Wapiti day bomber, arrived at Usworth in December of 1932. Evenings and weekends were the busiest time for Usworth as the part-time airmen turned out for training. The nucleus of regular RAF staff were allowed to take Tuesdays and Wednesdays off, thus effectively leaving the station deserted so that they could be present to train the Auxiliaries on a weekend. Training continued in earnest and in June 1934 No. 607 squadron proudly flew nine of their Wapiti aircraft in formation past its first Honorary Air Commodore, the Marquis of Londonderry. In the previous month the Wearside public had been given their first opportunity to view the work of the squadron at close hand when the station was opened for the Empire Air Day on May 24. This show attracted 1,300 visitors to the station, although it is reported that almost 5,000 other spectators watched the flying display from outside the airfield.

Empire Air Days were staged on an annual basis with the next one occurring on May 25 1935. Proceeds from these events went to the RAF Benevolent Fund, with admission being one shilling for adults and three pence for children. On the day the visitors were able to see fourteen aircraft on the station, including Avro 504s and Wapitis. Highlights of the day included formation flying by the Wapitis and the opportunity of sitting in a Wapiti for a small fee. When Usworth opened its gates to the public on the RAF 's Empire Air Day in May 1936, the flying display of all twelve of No 607 squadron Wapitis attracted a crowd of 3,500 people. In addition to these aircraft some new shapes in the form of the Avro Tutor and Hawker Hart trainer were present with No.607 squadron. This show probably marked the last public appearance of the Wapiti. This type of aircraft continued to fly with No. 607 squadron through until January 1937, even though on 23 September 1936 No. 607 squadron had been redesignated as a fighter squadron . With the squadron becoming a fighter unit the Wapitis were given up for the faster and more graceful Hawker Demons which started to arrive in late September of 1936.

From February 26 1937, a regular squadron, No. 103(B) flew Hawker Hinds from Usworth alongside 607. As the only regular squadron at Usworth, No. 103 squadron flew every day of the week leaving the airfield free for the Auxiliary boys and their Demons at the weekends.

Life on the station was always hectic and 103 Sqn had a set programme for the year, which included Bombing, Air Gunnery, Reconnaissance, Photography, Formation Flying, Night Flying and Instrument-Navigation Exercises. During this time the squadron went to a practice camp for 3 weeks for concentrated bombing and Air Firing at Catfoss and Bridlington. It was involved in the "Centurion" bombing trials with No. 15, 40 & 101 squadrons, 101 had Overstrands, the first turreted aircraft in the RAF. These trials were held at Tangmere and lasted 3 weeks - 103 was employed to photograph the bombing results on the radio controlled World War One battleship HMS Centurion.

Flying at Usworth was never very easy, as the weather conditions in the North East could be extremely bad indeed and industrial haze and smoke were great hazards. The pilots had little in the way of radio aids except W/T and flew by dead reckoning, map reading and "by the seat of their pants". They really flew in some shocking murk and the main guideline was that if they could see Penshaw Monument, they would get airborne! Even in 1937 they were really not much better off than WWI pilots !

The Empire Air Day in May 1937 was a roaring success with the local people and attended by thousands from Newcastle, Sunderland and Gateshead. No.103 squadron put on displays of formation flying, aerobatics and dive bombing, was well supported by 607 and by visiting aircraft from neighboring Air Force stations. A dummy fort near the southern perimeter was attacked by the Hinds of 103 squadron with the Demons of No.607 squadron defending. One Hind was 'shot down' and disappeared low towards the Wear, trailing realistic smoke. The climax was a fly past by nine Hinds , nine Demons and nine Audax of No.226 squadron from Harwell. Other visiting aircraft included three Gloster Gauntlets from No.19 squadron and a strange looking Boulton Paul Overstrand bomber. Unofficially the attendance had been out at over 20,000, however the official figures for paying visitors were 14,077. The attendance represented the fifth highest for all of the displays held across the country, the RAF Benevolent Fund gained £637, fourth highest, a sum equivalent to almost £500,000 in 1995. Thus the local people got to know the RAF and it was an excellent exercise in public relations.

Sadly the success of 1937 was not to be repeated in 1938 as the event was totally ruined by continuous rain on the day and cloud levels below 500 feet (about 150 meters). A Demon did take off and quickly disappeared into the murk, returning later to report that there was no sign of any improvement. After the Empire Air Day new equipment for No. 103 squadron, the Fairey Battle, started to arrive with the delivery of K9946 on July 18 1938. This was to mark the start of other changes at Usworth for by the time the unit was completely re-equipped it was relocated to Abingdon by the start of September 1938.

In August 1938 a Gloster

Gladiator from No.72 Squadron force landed at Usworth. It was repaired and made

airworthy but stayed at Usworth for in December 1938 No. 607 squadron also

started to re-equip with the more capable Gloster Gladiator. However the last

of the Demons did not leave until March of 1939. The addition of Gladiators was

certainly a step in the right direction as the aircraft had an enclosed

cockpit, good visibility, an excellent turn of speed for a biplane of over 400

kph and a hefty armament consisting of anything up to four .303 Browning

machine guns. At about this time the squadron identification codes changed from

LW- to AF-, so becoming 607's wartime code.

The departure of No. 103 squadron made way for the arrival of 'G' Flight of No.1 Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit on February 1 1939, operating Hawker Henleys and other types. This unit's stay was however quite brief as it departed on 19 May 1939.

Further development of the airfield commenced in September 1939 when work was started on laying two concrete runways. In addition to the laying of the runways the airfield was expanded to the south, east and west by taking in adjoining fields. The new 2,800 feet (about 900 meters) long runway was laid north-west to south-east, with another of similar length on a north-south heading. A new perimeter track was laid along the airfield boundary with eight dispersal pens, each capable of taking a twin-engined aircraft. Also along the track were thirty four hard standings for single-engined fighters. Also along the outer edge were nine slightly larger hard standings. Three of the old pre-war Callendar hangars were dismantled, leaving just the Lamella and one Callendar hangar opposite the main gate. Many additional building were constructed between the airfield and the road. An Operations room for the stations new role was built near the Lamella hangar. This Operations room was later supplemented by an underground Battle Headquarters near the Cow Stand Farm corner of the airfield.

On the North Camp much of the vacant land was taken up with new accommodation blocks for the expected large influx of personnel, including WAAFs. A new WT/RT station was set up to supersede the old hut. On both camps numerous air raid shelters were constructed. To assist in the defence of the airfield a series of dispersed sites were set up over a wide area around the airfield. These sites included a searchlight camp at the top of Ferryboat lane, and small AA gun posts out on the Birtley road, above the old quarries at the bottom end of Boldon Bank and along the disused railway line towards North Hylton. A large gunsite was set up near Downhill Farm and on the Birtley road, well away from the station a decontamination centre was built. Most of these dispersed sites were to be manned by members of the Durham Light Infantry and the Royal Artillery.

This work effectively rendered the airfield unusable and thus No. 607 squadron moved north to RAF Acklington, which they shared with the newly formed No. 152 squadron. This squadron were flying Gladiators, coded UM-, before receiving Spitfires in December of that year. However, it would not be long before Usworth's first unit would be called to action as they were to move to Merville in mid-November 1939 as part of the British Expeditionary Force.

Despite the lull in flying activity, Usworth was designated a Sector Fighter Station in No. 13 Group, Fighter Command and thus controlled the reporting of all raids on the area. The work on the runways continued into 1940 and was much hampered by severe frosts which delayed the reopening for flying until the end of March 1940. It was expected that the airfield would once again become the home for No.607 squadron. However, on 11 May 1940 new residents moved in from RAF Church Fenton. At 15:35 fifteen Spitfires from No.64 squadron arrived at Usworth and were dispersed around the airfield, becoming the first wartime residents a month after receiving its new Spitfires. The pilots were accommodated in the Officers Mess. The stay of No.64 squadron was to be extremely brief, for the threat to the South of England resulted in all of the aircraft departing for Kenley at 16:00 on 16 May 1940. Had it not been for this threat Usworth may well have become a Spitfire base.

Newly equipped with Hurricanes No. 607 squadron returned home when ten aircraft arrived from Croydon on 4 June 1940 to re-assemble and re-arm after their big show in France. The squadron received additional Hurricanes to replace those lost in France. During their time in France the squadron had been responsible for destroying over 70 aircraft of the Luftwaffe. Even at Usworth danger was ever present with two aircraft being destroyed in flying accidents. These being N2704 on June 26 and P2974 (AF-F) on September 9th.

Due to its role as a sector fighter station, Usworth was singled out for a major Luftwaffe attack during the Battle of Britain. On August 15 1940, a large force of Heinkel He IIIs of KG26, inadequately escorted by Bf 110s of ZG76, were detected approaching the east coast. Spitfires from No. 72 squadron at Acklington met them of the Farne Islands and although heavily outnumbered, claimed several destroyed.

The German formation then split in two, one section making for Tyneside, while the other turned south. The second Acklington squadron, No. 79, encountered the northern group just off the coast and a wild dog-fight with their escorts ensued. Reforming, the Hurricanes caught up with the bombers approaching Newcastle, where their primary objective would seem to have been Usworth, faulty intelligence indicating it to be a major fighter station.

Harried by the Tyne guns and more Hurricanes from Drem, the Heinkels made off, scattering their bombs to little effect and leaving Usworth untouched. No. 607 was called to readiness at 12:30, with the pilots waiting impatiently to be called into action. Finally at 1:15 the order came to scramble, with twelve Hurricanes setting off under the command of Flt Lt Blackadder, as Sqn Ldr Vick, the CO, was on leave. On the ground, those members of the squadron who had been in France wondered if this was going to be a re-run of the grim day when the airfield at Vitry was attacked by the Luftwaffe as No.607 took to the air. There followed a few confusing minutes during which No.607 squadron was sent off in several unproductive chases including one to intercept Heinkels that were reported over Usworth. These appeared to pass over without sighting the airfield which was largely shrouded in cloud. Eventually, the southern force was sighted and, fired on by Nos. 14 and 607 squadrons from Catterick and Usworth, jettisoned their bombs in the area of Seaham Harbour. The enemy lost eight bombers and seven fighters and since no military target was hit, it was certainly a highly successful defence on the part of No. 13 Group and the AA guns. No.607s tally for the day was four Heinkels without the loss of any Hurricanes.

Late on the evening of 7 September 1940, after three months of recovering, No. 607 squadron received instructions that they were to proceed at first light south to RAF Tangmere to join No. 11 Group of Fighter Command at the height of the Battle of Britain . The first wave of ten Hurricanes departed at 11:15 the following morning, to be followed by a further nine at 11:24. In the opposite direction twelve aircraft from No.43 Squadron left Tangmere for Usworth the following morning. Only eleven of these aircraft reached Usworth with L1727 (FT-R) crashing en-route. By 19:30 hours the other eleven aircraft were safely on the ground at Usworth. Bloody and battered, No. 43 squadron had come up from Tangmere for a rest period. In the thirteen days from the 26 August seven pilots had finished their operational trips in hospital and four more had died. Whilst at Usworth the unit saw no action but did suffer some losses with at least four aircraft being destroyed in flying accidents (L1963, V7303, P3527 and P2682) and the loss of two pilots. Whilst at Usworth the squadron received additional aircraft in September and October (including V7126, V6925, R4196, P3809, P3665, P3357, P3097 and L1963). On 13 December 1940 No 43 squadron departed to Drem in Scotland and No. 607 squadron arrived from Tangmere with nineteen aircraft in time for Christmas. Sadly the squadron had suffered whilst at Tangmere with fourteen aircraft being lost in accidents or action, including six aircraft on their first day in action on 9 September. On 16 January 1941 No. 607 squadron left for the last time when it moved north to RAF MacMerry in Scotland. From henceforth fighter defences were based at nearby RAF Ouston and until the end of the war Usworth was used in a training role.

This transitional period began back in 1940, when Usworth had been host to No. 3 Radio Maintenance Unit, which was tasked with repairing radar tracking equipment. The unit moved on in October and was replaced from February 1941 by No. 55 OTU, who completed their move from RAF Aston Down and officially moved in on March 14 1941, although 'F' squadron moved to Usworth on 8 February 1941. No. 55 OTU had been born out of No. 5 OTU on 1 November 1940, the units role being to train fighter pilots. Thus for over a year the roar of the Merlin was heard again, all be it attached to various assortments of Hurricanes.

As a complete unit No. 55 OTU also flew target towing Fairey Battles, for dual seat training an assortment of Miles Masters, Martinets, De Havilland Tiger Moths and possibly Harvards. A few Bristol Blenheim fighter bombers and Boulton Paul Defiant night fighters were taken on charge to cover different aspects of fighter pilot training. The unit's aircraft carried an assortment of identification letters, some are known to be EH, PA, UW and ZX, quite an assortment, possibly one per flight. From time to time Usworth would receive visitors of all descriptions, bringing in supplies, formal and informal visits and dropping airmen off on leave like a taxi service. Whitleys were frequent visitors bringing service men back from Canada and the States.

Pilots of many nations were trained by No. 55 OTU at Usworth, including Officers and NCOs these pilots included many Polish, Czech, Canadian, Australian, American, New Zealanders and small numbers from Latvia, Lithuania and even Ceylon. The training of new pilots up to operational status was a hazardous activity with there being many aircraft damaged or destroyed during the units time at Usworth. Many of these pilots have their last resting place in Castletown cemetery near the airfield. On April 25 1942, three days before the OTU moved to Annan, an overshooting Hurricane collided with the Lamella hangar, injuring the pilot.

With the departure of No. 55 OTU, the station was reduced to a skeleton staff for care and maintenance, pending a decision as to its future. This was not long in coming, however, as on June 23 1942 No 62 OTU formed here. The purpose of this new unit was to improve the quality of the training given to radar operators for the night fighter squadrons. No. 3 Radio School at Prestwick had previously been responsible for this task, despite a lack of facilities and ground trainers.

No 62 OTU took over the Airborne Interception (AI) Training Flight from No. 3 RS, consisting of 10 Ansons and an initial course of 24 pupils. The unit's projected establishment was to be three squadrons, each with 14 Ansons, 14 pilots and 14 observer-instructors. Each aircraft was fitted out as a flying classroom with duplicate AI indicators so that the instructor could monitor the pupil's interpretation of what was being seen on the cathode ray tube, while a second pupil watched the target's behaviour visually from the front seat as he listened to the commentary over the intercom. When the time came to act as the target aircraft, the pupils were expected to keep their pilot on track between two radar beacons, a boring but useful exercise known as 'beacon bashing'

After six weeks of carefully graduated exercises the majority of the trainees had gained such a sound grasp of the principles involved that they were able to adapt themselves to the higher speeds of operational aircraft. The perfection interception was to be able to look up from the screen and see the target aircraft ahead and slightly above at a minimum range of 300 yards (about 275 meters). From Usworth they went out to the night fighter OTUs to be crewed-up with their future pilots. There the team was moulded and finally prepared for service with a squadron.

No 62 OTU also trained a number of US Army Signal Corps officers as AI operators for USAAF Bristol Beaufighter squadrons early in 1943. In fact a there was detachment of the 416th Night Fighter Squadron at Usworth between May 14 and June 10 1943. For some time bad weather hindered the output of the night fighter OTUs and some 49 pupils were held at No 62 OTU until vacancies enabled them to graduate to the final stages of training. Throughout the OTU's stay there was only one serious accident, which occurred on February 19 1943, when two Ansons collided head-on three miles north of the aerodrome with the loss of eight lives.

Usworth proved to be inadequate for the rapid growth of No 62 OTU and the sparse living accommodation was stretched to the limit, and the installations of a balloon barrage at Sunderland was the final straw. Its proximity to the airfield made it a great hazard, especially in a locality where industrial haze often obliterated all landmarks in a very short space of time, so the unit moved to Ouston at the end of June 1943.

Just prior to the departure of No 62 OTU Usworth was to have a brief spell of Naval occupation when a detachment of aircraft arrived from No 776 squadron of the Fleet Air Arm on 5 Mar 1943. The squadron was headquartered at Speke, near Liverpool, and operated a mixture of aircraft including Blenheims, Rocs, Skuas and Chesapeakes. The purpose of the detachment is unknown as are the aircraft types brought to Usworth. This detachment lasted until 12 July 1943. Further Naval activity also occurred when Fairey Barracuda aircraft were later operated from the station alongside Grumman Martlets. Records of this use by the Fleet Air Arm are however sketchy.

Little flying took place from Usworth for some time after this and records show that it was being administered by RAF Morpeth for care and maintenance. In November 1943 the station was given over entirely to ground training when No. 20 Initial Training Wing moved in from RAF Bridlington. The role of this unit was to train Wireless Operator/Air Gunners and Flight Engineers, although the Flight Engineers course was never run at Usworth. The strength of the unit at Usworth was usually around 900 trainees which put considerable strains on the squadron facilities. During their stay the unit tried its best to improve the station facilities and even persuaded the local bus company to lay on two extra bus services to Sunderland as the station was considered to be somewhat isolated and the existing public transport totally inadequate. More emphasis appears to have been given to improving recreational facilities, accommodation and cooking facilities as the training programme. The airfield was little used for flying with only one aircraft landing in the whole of January 1944. The unit moved out by the summer of 1944.

Flying did return to Usworth when No. 31 Gliding School formed sometime in 1944, although it is known to have been before the middle of that year, with Falco IIIs and Cadets. Its job was to give elementary flying training to cadets of the Air Training Corps, from local squadrons in the north-east. An Aircrew Disposal Unit arrived on 24 June 1944, being responsible for finding posts for tour-expired aircrew, many from overseas. This unit was supplemented from 10 August 1944 when No.2739 & No.2759 squadrons of the Royal Air Force Regiment took up residence. Their stay was brief as they departed for overseas duty on 18 September 1944. The departure of the RAF regiment was followed quickly by that of the Aircrew Disposal Unit which relocated to Coventry on 22 September 1944. Once again the airfield reverted to care and maintenance under the control of No 14 Maintenance Unit, based at Carlisle. This unit retained control of Usworth through to 1952 and stored various items at the airfield, including parachutes and engines. At one stage several hundred Cheetah XIX engines were stored in their packing cases in the Lamella hangar.

For a time, the Gliding School had sole possession of the airfield. In 1946 a camouflaged Moth Minor was discovered in an MT shed. On instructions from their officer a group of ATC cadets broke the padlock of this shed, which was located just to the left of the main gate. The CO of the Gliding School was Flt Lt Jimmy Robson an ex-PR Spitfire pilot. He checked the Moth and he and a few other officers pooled their petrol ration coupons and obtained a few gallons of petrol from the nearby Three Horse Shoes pub which then had a pump. Flt Lt Robson flew the Moth on several occasions before the CO at RAF Ouston commandeered it and it was not seen at Usworth again !

By 1950, 31GS had received its first two seat glider, a Slingsby Sedbergh, number WB968. The somewhat hazardous use of single seater Slingsby Kadet Mk.1 gliders, for solo training, was continued however, the two seater being used to give experience of stalls and spin recovery action. This clearly helped reduce the high damage rate to the single seaters but the system of solo training using ground slides, low hops and then high hops was eventually to be superseded. Although this was just as well for all concerned, the old system was great fun. Winch drivers needed to be highly skilled for solo training - they could prevent accidents by the judicious use of throttle, playing the glider like a kite, using a burst of engine power to yaw the aircraft thus arresting the drop of a wing. Electrical insulating tape was used to bind the automatic cable release in the closed position so that the winch driver did not lose his pupil ! The same tape was also used to bind the loose ends of the many reef knots in the cable where breaks had occurred.

Anyone glancing into the hangar and seeing the jumbled matchwood which had at one time been a glider aircraft would never have believed that air cadet student pilots seldom received more than a few minor cuts and bruises. Gliders were retrieved to the launch point by 15 cwt Bedford trucks (these had replaced the previous "Beaverette" armoured cars which were initial issue) and instructions to the winch driver, a thousand yards away, were given by semaphore bats. The winches used Ford V8 engines and the gear box had four gears (and a reverse!). Cadets from the Air Training Corps finished their flying training when they achieved a solo glide of about 45 seconds to obtain their "A" certificate issued by the British Gliding Association under delegation from the Royal Aero Club. Improved methods of two seater training soon reduced the accident rate and made it possible to train cadets to "B" standard, involving three solo circuits of the airfield, taking about three minutes each.

In common with the other twenty-six Air Cadet Gliding Schools in Great Britain the staff consisted of unpaid volunteers, mainly civilian instructors and staff cadets, often recruited from those who had shown most ability on training courses. Apart from an outer layer of old flying clothing and helmets no longer required by the R.A.F., the personnel of the School wore whatever they pleased and often presented a motley appearance. Coming from all walks of life, their one common bond was an overwhelming enthusiasm for flying. In 1950, the Gliding School was billeted in the old sick quarters, formerly across the road from the guard room, adjacent to the Three Horse Shoes public house.

Towards the end of 1951, Jimmy Robson handed over the school to Mark Scott, an electrical engineer at Reyrolles and ex-National Service Captain, R.E.M.E. During the fifties the strength and experience of 31GS mushroomed, building the School to a leading position in the United Kingdom.

Initially the cadets and staff brought their own meals with them each weekend but as numbers grew, organised catering became necessary. The messing requirements for up to 20 staff and 10 cadet students began to become more complex. Returns had to be made to the Ministry of Food, as there were no R.A.F. messing facilities at Usworth. Interestingly, rationing in Britain did not end until 1954 (in Germany it ended in 1948!).

The Gliding School flew every weekend that the weather permitted, every Bank holiday, even Christmas Day as well as a fortnight's continued training each Summer. The living quarters were eventually moved to hutted accommodation near the threshold of runway 09 to the West of the airfield and a canvas 'Bessineau' hangar was erected nearby for the gliders. The cadet output had now reached nearly 100 solo pupils per year !

Powered flying returned to Usworth on February 1 1949 when No. 23 Reserve Flying School formed with Ansons, Tiger Moths and, later Chipmunks, disbanding at the end of July 1953. Other post-war units were 1965 flight of No. 664 squadron with Austers and No. 2 Basic Air Navigation School with Ansons. Durham University Air Squadron then moved to Usworth and their Tiger Moth aircraft operated side by side with the gliding activity. Much later, the Newcastle Gliding Club were also to fly from Usworth when their former site was unavailable.

On 18 April 1951 control of Usworth passed to No.2 Basic Air Navigation School. Usworth of the early fifties was then 2 Basic Air Navigation School, RAF, and a pretty busy place it was too - seven days a week. The student navigators were all regular RAF (mainly on National Service), but the pilots and instructors were RAFVR, all ex-RAF pilots and navigators. Airwork Ltd. of Cambridge had the contract to run the school, employing civilians to do the aircraft maintenance and overhauls. Most of the fitters were ex-RAF, but not all.

The aircraft used for training were Anson T.21's and there were about 25 of them on strength at that time. In addition to the Ansons there were about 15-20 Chipmunks, which were used by the Durham University Air Squadron - mostly at weekends - also maintained by Airwork. By and large there were Ansons dotted all over the airfield and the comparatively few fitters were kept really busy, it was common practice for one or two fitters to perform daily inspections on over a dozen aircraft in a morning.

About a dozen or so Ansons would go off every day for a 3-hour, 3-leg exercise, each aircraft carrying a pilot, an instructor, and 3 students. Once they had departed, tradesmen used to go into the main hangar and work on the Ansons undergoing overhauls and repair. In the centre of the hangar there was always an Anson jacked up on trestles undergoing a 'major', whilst other Ansons on 'minors' or repairs occupied the flying club half of the hangar. The other half of the hangar was home to the Chipmunks, which were brought in each night.

The Anson was very reliable, with not one instance of an airframe or engine failure of any importance during an awful lot of flying hours. There was one Anson crash however on 30 July 1951, but even that wasn't the fault of the aircraft. At the end of one of the training flights, a pilot decided to do a one-engine approach, overshot, lost critical flying speed and staggered along runway 23 at about 200 feet, tried to turn, spun in and went in near vertically into a field beyond the eastern boundary of the airfield (there were few houses there then - fortunately). It didn't seem possible that anyone could possibly have survived. A wing-tip had caught the ground first and the Anson cartwheeled over, absorbing a lot of the impact, there was no fire because the tanks were pretty empty. Miraculously the 3 students walked away from the wreckage with only bruises, the pilot and navigating instructor suffered broken limbs and eventually recovered.

The Basic Air Navigation Squadron was to operate from Usworth until being disbanded on 30 April 1953 when control of the station passed to Durham University Air Squadron. In 1955, the Auxiliary Observation Flight moved from Usworth and 31GS of 64(N) Group20 was named 641 Gliding School. In 1958, the Gliding School, the University Air Squadron and the G.C.I. aircraft were moved to Royal Air Force Ouston, as Usworth was to close. Some limited use was made by the Territorial Army for parachute training from tethered balloons.

On 3 July 1962, RAF Usworth, was purchased by Sunderland Corporation for £27,000 and reopened as Sunderland Airport. Sunderland Corporation re-laid the runways and renovated the hangar, and in June 1963 Sunderland Flying Club came into being. The following year an Open Day and commemorative ceremony took place on June 28 1964 to celebrate the rebirth of what was now Sunderland Airport. There was a modest flying display and pleasure flights were made available in a visiting Dakota. The cost of such flights was 15 shillings for adults and 10 shillings for children. The Dakota being kept busy all day. However, its short runways precluded any use on a regular basis by other than light twins.

The appearance of the Dakota in 1964 was a result of a brave attempt to operate a charter airline from Sunderland in the early 1960's - Tyne Tees Airways. Tyne Tees Air Charter Ltd was formed in early September 1960 by Mr Ghulam Mohammed, as an ad-hoc charter company, based at Newcastle Airport. Mr Mohammed was Managing Director of the company, with Mr T.D. Keegan (later of British Air Ferries fame) as technical advisor, and also provider of the company's initial equipment through his company Trans World Leasing. Commercial operations by Tyne Tees began from Newcastle on 6 September 1960, when the company's first aircraft, De Havilland Dove, G-AGNE, arrived from Stansted.

In 1962 Tyne Tees moved one step nearer the 'Big League' with the acquisition of their first Dakota, G-AJHZ, on 23 March, and this aircraft operated on a series of inclusive tour flights between Newcastle and Ostend, and also from Manchester to Perpignan throughout the 1962 summer season. This was more than could be handled by one aircraft, and so, a second Dakota, G-AMNV arrived on 1 June 1962 to help share the workload. At this time one of the airline's Doves left for charter work abroad, and on 23 May 1962, Dakota G-AJHZ did likewise, when it left for Spain on charter to the Spanish carrier TASSA, to be joined on 27 November by sister aircraft G-AMNV.

In July 1962 Tyne Tees Aviation Engineering made the move from Newcastle to set up the airline's engineering base there at the newly opened Sunderland Airport. All the airline's maintenance and overhaul work was transferred to Sunderland, and during January 1963 several aircraft of the fleet that had seen little use during the previous year were delivered to Sunderland for storage. These aircraft included Dragon Rapide, G-ALPK, De Havilland Heron 1 G-AOZM (leased from Keegan Aviation in January 1963 but never used), and Bristol 170 freighter G-AILW (leased as G-AOZM).

Meanwhile, charters had been fixed up for the 1963 inclusive tour summer season and on the strength of these, Tyne Tees acquired a further two Dakotas in April 1963. The first of these was G-AOXI, which was historically noteworthy as being one of the two Dakotas converted by BEA to turboprop power with 2 Rolls Royce Darts in 1950. When it flew into the Tyne Tees base at Sunderland on 8 April 1963 however, it had long been converted back to the usual Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasps. Despite being such a famous aircraft, G-AOXI never went into service with Tyne Tees, and languished in storage at Sunderland until being broken up in late 1965. The second Dakota to join Tyne Tees that year was G-APUC, and this aircraft arrived at Sunderland on 23 May 1963. G-APUC20 was actually handed over at Gatwick on 4 April, but was delayed from moving to its new home by a couple of jobs in the South of England and a trip to Luxembourg, as well as two days crew training in addition to a short term charter to Autair.

For the 1964 season the two Dakotas leased to TASSA, G-AJHZ and G-AMNV, were returned to Tyne Tees at Sunderland. During 1963 and the early part of 1964 a rationalisation of the Tyne Tees fleet took place and several of the smaller aircraft were sold off. In April Heron G-AOZM, and Riley Dove G-ARTK left, followed in July by Auster Alpine, G-AOGV, DH Dove G-AMHM and Piper Apache G-ARHJ. In November Bristol Freighter, G-AILW was disposed of. Further rationalisation followed in March of 1964, when the airline's hardworking Dakota G-APUC was also sold off. Most of Tyne Tees' business was then centred on the two remaining Dakotas, and as a result all the other aircraft were sold. On 3 October 1964, G-AMNV positioned empty to Birmingham from Sunderland, leaving there for Le Bourget on a holiday package the same day. It returned to Newcastle via Birmingham on the 5th. On October 29th G-AMNV flew a freight charter from Carlisle to Ostend via Southend, and returned to Newcastle on 31 October. In the first week of November G-AMNV went on a charter flight to Scandinavia, and whilst this aircraft was away, Tyne Tees formally ceased to operate. Subsequently G-AMNV was flown home in December 1964, to join G-AJHZ which had been withdrawn and placed in storage in July at Usworth. In January 1965 Tyne Tees was placed in the hands of liquidators and the two Dakotas were sold off to cover accumulated debts.

The Air Day in 1964 became an annual event with subsequent shows attracting greater participation. For 1965 the organisers had arranged for a Sopwith Pup to give a flying display. However the static display was dominated by a Beverly from the RAF. In 1966 the flying display included participation by the RAF with a Shackleton, Jet Provost a Whirlwind and the Red Arrows, the show was attended by in excess of 17,000 spectators. The Air Day in 1967 followed much the same format of the previous year. For many the highlight of the 1968 Air Show was the appearance of the North American P-51D Mustang owned by Charles Masefield. This classic World War II fighter put in appearance in it special red racing scheme. However the show was closed with a solo aerobatic routine by an RAF Lightning fighter.

A further Air Show was held in 1969 with the only military flying coming from those units of training command based in the area, including Chipmunks and Jet Provosts from Ouston and a Whirlwind from Acklington. After the brief use by Tyne Tees, Sunderland Airport started to develop as a thriving light aviation centre. Parachuting and gliding completed the varied activity. Sunderland Airport was rarely to see any significant activities for the remainder of the decade, except for the arrival in 1969 on an ex-RAF Vickers Valetta for use as a club house by the flying club. The regular circuits of light aircraft where to be occasionally interrupted over the following years by the arrival of other RAF aircraft, some expected, others not.

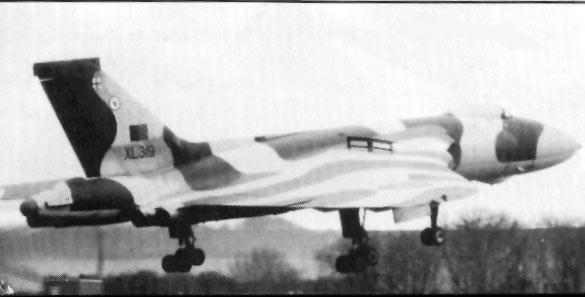

Airshows made a reappearance in 1973 when the undoubted highlight was the return to Usworth of an airworthy Hurricane fighter to recall the days of the early 1940s. The Hurricane was supported by the Lancaster and Spitfire from the Battle of Britain Flight . Other noteworthy participants included a Vulcan bomber, Gloster Meteor and De Havilland Vampire.

On 28 August 1974 the peace of the aerodrome was to loudly interrupted when a Royal Air Force Buccaneer strike aircraft carried out an emergency landing on Runway 23 without warning at 14.05. The aircraft had been on its way to carry out a practice attack on a bombing range in Northumberland when it suffered a bird strike. With the navigator injured and the canopy shattered the pilot, an American on an exchange posting, had declared an emergency. The runway at Newcastle had been cleared ready for the aircraft's arrival, when to everyone's surprise the aircraft touched down at Sunderland, even though the runway length was marginal, indeed the aircraft overran the runway. By 1420 an RAF guard had arrived from RAF Ouston with two armourers to make safe four practice bombs. Meanwhile the crew had been taken to hospital by helicopter. By the end of the day the aircraft had been placed in the main hangar. A repair crew arrived and a replacement canopy was flown in by an RAF Andover and the aircraft was repaired and departed, with Sunderland returning to normal.

The day to day business of the airport continued with the ground facilities being enhanced gradually. A second small hangar was erected. By 1976 the airfield could boast 23,376 aircraft movements and 5.419 passengers and 29,242 movements with 7,182 passengers in 1977. The Red Devils parachute team used the airfield as the base for their Islander aircraft in 1977 while doing parachute drops at the Tyneside summer Exhibition in Newcastle.

One of the largest number of movements on one day occurred on 30 June 1979 when Sunderland Airport was chosen as the refuelling stop for over seventy vintage De Havilland Tiger Moths, Hornet Moths and Gipsy Moths taking part in a rally to mark the 50th anniversary of the Gipsy Reliability Tour of 1929. The aircraft arrived at Sunderland from Hatfield via Hucknall and flew on, after refuelling to Strathallan in Scotland. From about midday there was intense activity at Sunderland as the brightly coloured biplanes landed, were marshalled and fuelled, then took off again at two minute intervals..

The last Sunderland Air Day took place in on 15 June 1980 and was perhaps the largest and noisiest display to be held at the airport. The flypast included many RAF aircraft including the Jaguar and Nimrod. Vintage aircraft were represented by the Spitfire, Hurricane and Lancaster with the support of the Firefly, Meteor and Vampire. Many civil residents from the airfield were also displayed.

More military aircraft were to arrive from 1975, this time in bits for the recently established North East Aircraft Museum. The Museum aircraft were parked near the Lamella Hangar. It was this collection that was to bring in the largest aircraft ever to land at Usworth. It was on Friday 21 January 1983 that Avro Vulcan B2 XL319 was to touch don at Usworth, after nearly one years delay due to the Falklands crisis.

RAF Waddington gave the Airport authorities 48 hours notice to organise fire-cover, the local brigade providing 4 appliances to supplement the 2 airport tenders, plus an ambulance to comply with the RAF's conditions for landing. The local police were informed to control crowds and parking, which required an overflow area on the disused driver training school.

On the Friday morning, RAF Waddington called to say that the ETA would be delayed from 11.00 a.m. to 11.30 a.m., however at 11.00, a call went up "It's coming !" as the shape of the large delta came into view from the south, there was then a rush as everyone ran to get into position to photograph the landing.

XL319 made a large circuit followed by a low flypast down the runway. Sqn Ldr MacDougall radioed the tower to say he would make one overshoot then a landing, as he made another gentle circuit. He came in low over the hill and the housing estate at the east end of the runway, the undercarriage gently touched the runway for a few seconds until the throttles were opened and the Vulcan accelerated away making a noise that only a Vulcan can, turning tightly back into the circuit for a final time. Sqn Ldr McDougall touched her down on the end of the runway and deployed the brake chute, later he said he could have stopped halfway down the runway, however he taxi-ied on to the end for the benefit of the Press, after releasing the chute he turned left off the runway and taxi-ied along the perimeter track to a disused World War Two dispersal, which would be a temporary home for the Vulcan until the grass near the Museum dried out. The aircraft was turned around on the hard standing to facilitate towing later, a BBC camera man who did not move when he was told was blown back across the field for about ten feet as the jet blast swept around, however the only damage suffered was to his pride.

Sadly the high spot of a Vulcan landing at Usworth was to prove to be almost the last significant event for the airfield, for shortly afterwards the local council announced that the airfield was to be closed as it had made a loss and was the preferred site for the Nissan Car Factory. Fortunately Sunderland Council offered an adjacent site for the museum so its survival was guaranteed.

Nissan decided to retain the large Lamella hangar erected in 1929, for storage and garage facilities. However the runways would be lost under the factory's vast expanse. Usworth closed at 1500 GMT on May 31 1984, most of the departing aircraft making low passes and generally beating up the field. The RAF sent a Jet Provost to pay their last respects and airport manager, Bob Henderson, fired off a few shots from a Very pistol as the flag was lowered. As the airfield fell silent the bulldozers moved in and so vanished another British airfield.

And finally what of 'George the Ghost', who according to local folklore is a Canadian pilot killed in a Hurricane crash. Over the years there had been many sightings of his shady figure in the Lamella hangar and on occasion in the flying club bar. Will George finally find his rest now that the sound of aeroengines are no longer heard ?

I hope you enjoyed this fascinating insight into the Men and Machines of 607 Squadron.

ALL CONTENT

©2003GazetteArchive

FZC Publications

UK

Buccanear

Productions

_-+An on-going Gazette

Feature+-_

A CENTURY OF

FLIGHT

10

War in the

Pacific: From Pearl Harbour to Midway

The United States was caught by surprise on the morning of December 7, 1941, when 365 aircraft—bombers, fighters, and torpedo aircraft—attacked the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and sank or severely damaged eighteen warships, destroyed or damaged 347 aircraft, and left 2,403 dead on the ground.

The reaction of the United States was outrage at this undeclared act of war, and the United States declared war on Japan the next day. Three days later, Hitler and Mussolini declared war on the United States, making the conflict truly a world war. At the time of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. aircraft carrier fleet was out on manoeuvers and thus escaped attack.

However, the effect of the Pearl Harbor attack was to bring the United States and Japan into a closer state of military parity. Although the attack, and the December 13 attack on the U.S. airfields in the Philippines (which somehow also came as a surprise), gave Japan the momentary edge, and the United States would be involved in a theater of war on the other side of the globe, the industrial output of the United States would clearly make up the shortfall in a year or so. The strategy of the Japanese government in 1941, as it had been twice before in the century, was to fight a limited war until it gained its objectives, and then dig in. The attacks on Pearl Harbour and the Philippines were designed to buy the time needed to create new boundaries in the Pacific.

That the war turned into a contest to the death was due in part to the unwillingness of the Japanese military and the American political leadership to think in such equivocal terms. The fighter aircraft that Japan used to achieve early control of the skies were, as has been pointed out, derived from American and British designs (the Germans were much more circumspect about sharing their technology with their Japanese allies), but the designers a at the chief manufacturers—Aicihi, Kawanishi, Kawasaki, Mitsubishi, and Nakajima—took those ideas and pushed then in new directions that astounded aircraft designers the world over.

Moreover, unlike the Germans, the Japanese kept developing their aircraft and creating innovative designs. In fact, sometimes new models of older fighters (like the A6M3, a new model of the A6M) were given new designations because they looked like new airplanes even to trained observers.

The greatest of these fighters, on a par with the Spitfire and the Bf 109, was the Mitsubishi A6M Reisen, identified officially by the Allies as “Zeke,” but known throughout the war as the Zero. The Zero had a manoeuverability that seemed physically impossible to American pilots; finding its weakness became a top priority.

Painstakingly (and sometimes heroically), pieces of downed Zeros were recovered and brought to Wright Field in Day ton, Ohio, and pieced together. The engineers found that the engine was modelled on an old Pratt & Whitney that had been abandoned because of difficulty it had in diving, and that the plane had virtually no protective armour. The strategy developed for fighting Zeros was to avoid engagements at close range, to attack from above, forcing it to dive, its most vulnerable flight phase, and to use wide-area explosives that would disable the aircraft with even a glancing hit.

The key to the defeat of the Japanese air force was not in the tactics used against the Zero, but in the limited capacity of Japan to manufacture planes to replace those downed. Of the five important Japanese fighters deployed during the war, the Zero was produced in the greatest numbers, but production reached only about 10,500.

The Battle of the

Coral Sea in May 1942 was the first air battle

fought

exclusively between aircraft carriers that never saw each other.

The United States

lost the USS Lexington (shown, with the crew

abandoning ship

as ordered) with thirty-three planes aboard,

but the Japanese

were thwarted in their attempt to capture

Port Mores by,

New Guinea, which would have cut off

Australia from

the American fleet.

Outnumbered in the air three-to-one, the Japanese were fighting a losing battle the minute the United States entered the war. Two different philosophies informed the production of Japanese planes during the war. That the Japanese military supported both and gave proponents of each free rein to develop, make their mistakes, and come back with new machines showed intellectual fortitude, during what was, after all, a time of war.

The one approach had its roots in the ancient martial disciplines in which the weapon was an extension of the warrior. The pilots of these aircraft were all steeped in the martial art of Kendo and practiced as much with bamboo Shinai as with their training aircraft. The Nakajima Ki 27 Nate, built in the mid 193Os, was a paradigm of economy and miniaturization: a wing span of only thirty-seven feet (11 in), a length of less than twenty-five feet (7.5m), and virtually nothing between the pilot and the air save a thin metal skin so loosely riveted that pilots felt the draft of the onrushing air while in flight.

The Ki 27 was manoeuverable as few fighter aircraft before or since, and it remained in production throughout the early stages of the war. The design approach of the Ki 27, the brainchild of Hideo Itokawa and Yasumi Koyama, was carried forth into the Ki 43, a larger aircraft that maintained its predecessor’s agility, but at higher speeds. The plating protecting the plane was still tissue-thin and the weaponry was still minimal, but the plane had a larger cross- sectional area, all of which made the Ki 43 vulnerable (to some, more so than the Ki 27). The two Nakajima planes became the mainstays of the Japanese Army and were used throughout the Pacific for most of the war.

Meanwhile, the success of the navy’s A6M Zero, a decidedly Western airplane in conception, fostered the second design path the Japanese followed. The Zero gave rise to the Ki 61 Hien, a plane that melded the features of the Zero with those of the Polikarpov 1-16 used by the Soviets against the Japanese in 1939. The basic problem with the Ki 61 was its engine, a modified version of an outdated Daimler-Benz engine supplied by the Germans. The Ri 61 was most useful in defending Japanese targets against Allied bombers and fighters and in any area where it was likely to encounter ground fire or fire from enemy aircraft, resistance the other Japanese fighter could not withstand.

The two) basic approaches came together in he Ri 84 Hayate, a Nakajima fighter designed by Yasumi Kovama that combined adequate protection and structure; significant armament, and as much of tile agility that the design could incorporate. “Frank” fighters entered the fighting in 1943 and some thirty-five-hundred were built, but it was too little too late to alter the course of the war significantly.

The Hayate was seen by experts as the best Japanese fighter of the war. In May and June of 1942, two battles, fought at great cost to both sides, marked the turning points in the war: the Battle of the Coral Sea (fought May 2-8) and the Battle of Midway (fought June 4-.7). Both were called naval battles, but they were fought by ships that never saw one another and never, in fact, fired directly on an enemy naval vessel. In both battles, the objectives were very similar: the Japanese were seeking a foothold that would allow them to isolate Australia from the American fleet, and the Allies were determined to stop them. Both battles ended with the Japanese being forced to retreat, but whereas the Japanese claimed victory at the Battle of the Coral Sea because the Americans sustained greater losses, no such claim was possible at Midway. The Japanese lost four aircraft carriers and more than 330 aircraft to the Americans’ losing only the Yorktown and 150 aircraft. Midway was also the first battle for the CV 6 Enterprise, a name that was to become synonymous with excellence in naval aviation.

The American Fighter Planes

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbour, the fighter aircraft in the U.S. Army Air Corps were outclassed by both their Japanese and German counterparts, but the industry had been developing at a rapid pace for peacetime and had the momentum, the industrial base, the economic foundation, and the will and talent to catch up. The key individuals in bringing this about were Alexander P. de Severskv and his chief designer, Alexander Kartveli.

Throughout the war, they would he at the forefront of fighter design, urging the government and the military to make the greatest demands of, and place the greatest reliance on, the nation’s aircraft. The two prewar aircraft produced by the de Severskv- Kartveli team at Republic Aviation were the P-35 the plane that took America into the modern age of fighter aircraft, and the P-43 lancer, more heavily armed than the P-35 but paving for that armament with poorer performance.

Both planes were sent to air forces overseas and became the stopgap foundation of later fighter fleets. Another prewar fighter that excited the U.S. military was the Bell P-39 Airacohra, a sleek and agile aircraft that had the remarkable addition of a 37mm cannon that shot rounds through the propeller’s disc. With four machine guns and the ability to carry five—hundred pounds (227kg) of bombs, the Airacobra in all its many versions was a versatile and formidable weapon.

Curtiss P-40

Warhawk

Grumman P6F Hellcat

Some ten thousand of them were produced during the war and many were shipped to air forces overseas. The U.S. Air Corps kept having problems with the plane because Bell kept changing the engine specifications and thus its performance. The Airacobra became the basis of other successful fighters, but it was not a favorite of the Army Air Corps. (In June 1941 Congress established the U.S. Army Air Forces, virtually an independent branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, under the direction of Major General H.H. “Hap” Arnold. The USAAF was made into the totally autonomous U.S. Air Force—USAF—via the National Security Act of 1947 in September of that year.)

The most important fighter of

the early years of the war was the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, designed by Donovan

Berlin as an extension of the old Curtis Hawk of the early 1930s. The P-40 was

important not because it was a very good fighter—it was not particularly fast

or agile and performed poorly at high altitude—but because it was very reliable

and sturdy, which was important if the plane were to see action far from

suppliers of spare parts. More than 13,700

P- 40s were produced during the

war. Built primarily as a defensive fighter for patrol of the American

coastline, it was ill-suited for the aggressive open-sky dogfighting it would

encounter in war. It was the P-40 that was used by Claire Chennault in China in

early 1942 when he commanded the American Volunteer Group known as the “Flying

Tigers.” The plane lent itself to being painted with menacing shark’s teeth

(which inspired the group’s original name, the “Flying Tiger Sharks,” which was

later shortened).

The Flying Tigers, under Chennault’s gritty leadership (seldom has the field of battle witnessed so forceful a jaw as Chennault’s), downed 286 Japanese airplanes while losing only twenty-three of their own. The experience gained in these encounters, many with superior Zeros and other fighters, proved helpful in creating fighter tactics and the next generation of American fighters. The first American fighters to enter the war comparable to enemy aircraft then in the sky were the “Cat” fighters produced by Leroy Grumman and his chief designer, William Schwendlei beginning with the Grumman F4F Wildcat. The Wildcat was not a fast plane either —in fact, it was among the slowest fighters in the air during the war—but it had other features that made it useful. It was extremely durable and very short (shorter even than the old P-3 9)., and the fact that its wings folded at its sides, made it perfect for aircraft carrier use.

An American carrier could hold nearly twice the aircraft of a comparably sized Japanese carrier. (During some early encounters, the Japanese sent out patrols looking for the other carriers all these aircraft must surely be coming from.) As the size and capacity of carriers grew, so did the Wildcat, and it eventually inspired the F6F Hellcat, introduced in 1942: the plane that outfought the Japanese fighters. The Hellcat was the fullest expression of the American approach to meeting the Zeros and turning the battle to their advantage. In a typical dogfight, a Zero would have to score a direct hit to knock out a Hellcat; a Hellcat’s six machine guns had only to strike a Zero to disable it.

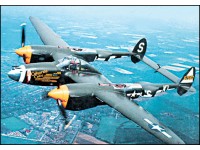

Since the Hellcat was faster than the Zero in straight flight, it could easily pursue and finish off its adversary. Some eight thousand Wildcats and nearly 12,300 Hellcats were manufactured during the war, making Grumman the largest producer of American fighters and the Cat series the most prolific of the war. America took the forefront of fighter aviation with the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, an airplane of astonishingly original design. This aircraft, first deployed in January 1939, was fast, agile, durable, and reliable, and could stay in the air longer than any fighter then in use. To prove its advantages, during tests it flew coast to coast in seven hours and two minutes, and would have broken the record then held by Howard Hughes had it not stopped twice along the way to refuel and test its equipment.

Lockheed P-38

Lightning

The essence of the Lightning’s innovation was the twin boom that housed the engine and propellers, leaving the centre component free for control, armament, and whatever else was needed. Giving speed, agility, and a solid reliable landing mechanism to an aircraft this heavy (heavier than some bombers) was no easy task. Hap Arnold was a firm supporter of the Lockheed P-38, and its designers, H.L. Hubbard and Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, adapted the plane to many uses, includ-ing bombing; this aircraft clearly inspired the effective night-fighter, the Northrop P-61 Black Widow. Some ten thousand P-38s were built, and this plane was credited with being used to shoot down more enemy aircraft—including the plane that carried Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander of the attack on Pearl Harbour—than any other American fighter over the course of the war.

Aerial Assassination of Admiral Yamamoto: April 18, 1943

Among the routine decoded Japanese radio traffic was word that Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, was conducting a one day inspection of bases in the Solomon islands. Included in the decrypts was the Admiral's complete schedule down to the minute. The information quickly moved up the chain of command and Nimitz ordered the P-38 Lightnings of the 339th fighter squadron to attempt an interception.

Fitted with special drop tanks for the 600 mi (965 km) flight from Henderson field the P-38s arrived near the small island of Bougainville right on schedule. After a minute or so the enemy planes were spotted and the attack began with most of the Lightnings climbing to give cover and engage the Zeros flying escort. Four planes closed on the first Betty bomber carrying the Admiral and after two broke off the remaining pair pursued the bomber down to the jungle and in a confused affair riddled the bomber with bullets until it crashed. The second Betty with Yamamoto's chief of staff, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, was shot down as well.

The best American fighter of the war, and arguably the best fighter of any nation and even the best propeller-driven fighter ever flown, was the North American P-51 Mustang. Its beginnings, however, were anything but auspicious; it was one of the few planes whose very designing made news. The RAF, frantic to procure more aircraft in 1940, offered a contract to North American to build the Curtiss P-40 with Allison engines. The president of the company, J.H. “Dutch” Kindelberger did not care for this arrangement (mainly because the licensing fee to Curtiss- Wright was too high), and offered to build a fighter for the RAE that would surpass the P-40. The RAF accepted the offer on the condition that a prototype of the aircraft be ready 120 days later.

On October 4, only 102 days after accepting the challenge, the prototype, designed by Raymond H. Rice and Edgar Schmued, was ready—except for the engine. Allison never believed that North American would meet the impossible deadline and dawdled on delivery of their V-1710 engines. The first test flights were held on October 26, but the prototype was damaged when the pilot hastily took off with an empty fuel tank and the plane cut out shortly after take-off. It was clear from the outset that the Mustang had a clean line and performed better than the P-40, but it did not climb well and performed poorly at higher altitudes, where it could be expected to see much action.

North American -

Mustang P-51

It turned out to be fortuitous that the designers of the P-51, not having actual engines to install, had been careful to allow a bit of extra space for the engines. In September 1942 British engineers noticed that the engine casing of the Mustang could accommodate the new Rolls- Royce Merlin engine. With the Merlin powering it, the Mustang was a new plane. Its top speed jumped to 440 miles per hour (7O8kph), tops for a single-engine fighter and it climbed to twenty- thousand feet (6,096m) in half the time. The performance of the plane at all altitudes was virtually the same and uniformly spectacular, and production of the hybrid aircraft was stepped up. The P- 51 Mustang became the most produced fighter of the war, with just under 15,700 made. The model P-S1D had a streamlined fuselage and a cockpit canopy that provided the pilot a full 360- degree view; the P-51D was thought by pilots to be the ultimate propeller-driven fighter.

If the Mustang had a challenger to these titles, it was from another American airplane: the Vought F4U Corsair a fighter good enough to remain in production for ten years after the war. The concept behind the Corsair, designed by Tex B. Beisel was to marry the most powerful engine then available, the Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp, the first 2,000-horse power engine, with the smallest possible airframe. In all the early designs, the size of the engine demanded a large fuselage, a large wing structure, and the largest propellers of any fighter in the war. The combination fell apart when a large undercarriage was necessary to support everything. Beisel’s ingenious solution was to design the wings in an inverted-gull-wing configuration and put the landing gear in the wings. This not only saved space in the fuselage, but also allowed for smaller, lower-to-the- ground landing gear. The result was another distinctive fighter design, but the aircraft was beset with many problems in the early going. The large and bulky fuselage cut down on pilot visibility, and the plane had trouble landing on the tightly confined surface of an aircraft carrier. The Corsair operated from land bases for three years until it was ready in 1943 to become a part of the carrier-based fleet of fighters.

TO BE CONTINUED................

ALL CONTENT

©2003GazetteArchive

FZC Publications

UK

Buccanear

Productions

ALL CONTENT ©2003GazetteArchive

ALL CONTENT

©2003GazetteArchive

FZC Publications

UK

Buccanear

Productions

EURO Group Guide to

Common Acronyms

and Terms

Civilian/Military

Why not print out this article for quick reference? It will build into a comprehensive document - extremely useful.

Aviation Glossary U/V

UA -

Unauthorized Absence

UAV - Unmanned Air Vehicle

UBC- Unbalanced Current